Project Description

My Personal Experience with Ramadan

Posted on 15/10/2012

DETAILS

Before leaving for Turkey I gave myself a personal promise to fulfill: to participate in the actual experience of fasting throughout my sojourn as it also coincided with Ramadan, which began two days prior to our departure. I made this decision for various reasons: to deepen my understanding of Islam from a practical/experiential point of view, rather than purely academic; to demonstrate my respect for my Muslim students and Islamic tradition (once my students knew of my decision they gave me their wholehearted support and guidance); and, to show respect while in a Muslim country during Ramadan. Joining the fast would also give me more of an insider perspective and appreciation of Islam and further my spiritual development.

Before the trip, I understood the meaning of Ramadan from an intellectual point of view. Ramadan is the holy month, which marks the period the Qur’an was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. Muhammad is Allah’s last Messenger who, through the revelation of the Qur’an, embodies the final completion of Allah’s message to humankind beginning with the prophets mentioned in the Judaic and Christian traditions.

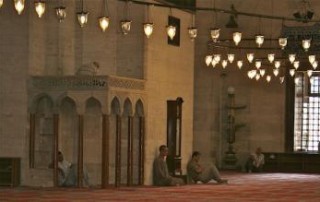

What I did not know beforehand was the extra rationale for fasting during Ramadan to mark this event. Fasting, the conscious denial of food and drink, allows us from choice to experience for a short time the pangs of hunger and thirst which countless others have neither chance nor choice to escape from. This daily fasting increases our awareness both of the suffering of others AND our appreciation, which we so easily tend to forget, of being able to eat and drink whenever we choose. The daily fast is a communal activity within the ummah without distinction of one’s economic, educational, social or political background. We are all one on an equal footing, unaware and uncaring of hierarchical positions, just the same as with daily prayers where everyone, rich and poor, line up together to worship Allah.

During Ramadan I did not eat or drink from sunrise to sunset. Actually, the fast began an hour or so before the sun rises. I would have Sahur, the meal that opens the fast, before 04:00 and end the fast with the Iftar meal depending on the time the sun set on that day. While in Turkey, depending on where I was, that could be 20:34 in Istanbul and 20:24 the further east we went (in Hong Kong, the sun set earlier, shortly before 19:00), giving me an average fasting day of 16 hours.

The first day was the most difficult for me. As a Buddhist I will fast on special days and when I was a Theravada monk I had no food after the mid-day meal (but I could drink!), so going for a long period without food is not difficult for me. The challenge came with the prohibition on drinking during the period of the daily fast, especially in the hot weather in Turkey. My throat quickly became parched, dry and difficult to swallow. I would frequently lick my lips in an endeavor to simulate the sensation of drinking. My fellow group mates would tease me, tempting me with delicious food and cool drinks but I persevered.

It is hard to describe the sensations that I felt at the first Iftar meal. I broke the fast by drinking water and eating dates. The shock of the cool water coursing down my throat enhanced my awareness and appreciation of the simple act of drinking water. Also, I became vividly aware of how others, less fortunate than I, suffer from loss of liquids and food. This was also a vivid act of instant awareness and mindfulness; experienced each night when I broke the fast.

I quickly fell into a daily routine of waking at 03:00 for Sahur, read some selections from the Qur’an and went back to sleep at 04:00. My Sahur was very simple: fruit, cookies, water and a yogurt drink. On a few occasions when I had Sahur with local Muslims, my fare was a bit richer. At the daily Iftar, I remembered not to gorge myself, or the reason for fasting would be negated. I ate just enough to feel comfortable, to keep my belly one third full.

We experienced Iftar in family settings and on a couple of occasions in larger communal surroundings such as having Iftar with staff and families of a school. I would just like to add here, that upon my return to Hong Kong, I went to Kowloon Mosque for Iftar with my student Ali. The dining area was packed (men and women eating in separate areas). The Imam led with prayers before we ate. This Iftar was the simplest I have had but, in its special way, one of the most meaningful. The food was simple: halim (type of soup), samosa, and juice. Following the meal, some people went upstairs for evening prayers while others remained in the dining area. They moved the chairs so they could stand in rows and pray. The sincerity of their devotion was most palpable and moving.

Wherever I went in Turkey, I was treated with openness and kindness. I always began with the greeting of peace, Wo assaloaleikum, and they were curious and pleased when they discovered I was also fasting. On this trip I fasted with our hosts Mehmet, Joseph, and Mr. Yelbay (but someone had to give up for one day due to illness). They were surprised and in the first few days, extremely solicitous to make sure I was all right. They asked me each day at the beginning if I would continue to fast, to which I answered in the affirmative. In addition, my room-mate Pauli said he would fast for one day but he was very sneaky (or fortunate) because he chose the day we spent most of the time in the air-conditioned van, sleeping. I tried to get him to continue but he turned me down, only saying he would continue with the vegetarian diet.

I continued my fast for the rest of Ramadan when I returned to Hong Kong, so I fasted a total of 25 days. Next year for Ramadan in addition to fasting, I will also endeavor to read the whole Qur’an, an Islamic tradition during Ramadan.

Buddhistdoor International

John Cannon

2012-10-15

For more articles about Interfaith Travel to Turkey

在啟程前往土耳其之前,我對自己許下了承諾,要在當地逗留期間體驗齋戒生活。而我們出發前兩天,恰好就是當地齋戒月開始的日子。事實上,有很多原因促使我做這個決定:首先,我希望從體驗、實踐的角度,而非純學術的角度,去深化我對伊斯蘭教的了解。而且,我想以此證明我對我的穆斯林學生,以及對伊斯蘭傳統的尊重(記得當時我的學生知道了我這個決定後,他們發自內心地全力支持我,又給我有關齋戒的指引)。此外,身處一個穆斯林國家,在齋戒月期間參與其中,是對當地傳統的尊重。相信齋戒亦能讓我深入了解並且更欣賞伊斯蘭文化,對我的靈修有很大幫助。

出發前,我對伊斯蘭齋戒月的理解建基於知識層面。齋戒月是神聖的月份,標誌著《可蘭經》啟示先知穆罕默德的時期,而穆罕默德是真主的最後使者,通過《可蘭經》的啟示,從猶太教和基督教傳統中的先知開始,讓人類體會真主傳達的信息。

除此以外,在齋戒月期間禁食,原來還有一個我事前不知道的理由。齋戒期間,有意識地拒絕進食任何食物和飲料,讓我們在有選擇的情況下短暫體驗飢餓和乾渴的痛苦。但是,這卻是無數人沒法選擇、不能逃避的生活。每天的齋戒,令我們更加意識到他人的痛苦,以及我們的富裕--我們常身在福中不知福,忘記自己有這個福氣,能夠隨意選擇每天所吃的食物和所喝的飲料。

齋戒月禁食是伊斯蘭民族一個無分經濟、教育、社會或政治背景的公共活動。我們都在一個平等的基礎上,完全不分階級地位,就如每天的祈禱集會中,每個人不論窮富都連成一線,一起敬拜真主一樣。

在齋戒月期間,從日出到日落我都不吃不喝。其實,齋戒是在太陽升起前一個小時左右就開始,在早上四點前我會吃上一頓封齋飯 (Sahur),然後開始一天的齋戒。齋戒過後吃開齋飯 (Iftar)的時間,取決於太陽下山的時間。而在土耳其,開齋飯的時間則取決於我所身處的地方;若我身在伊斯坦貝爾,吃飯時間為20:34,若我進一步往東走,吃飯時間卻會是20:24(香港的日落時間為大約19:00,較土耳其早),這樣算來,我每天平均齋戒的時數大約為16小時。

第一天的齋戒對我來說最難過。作為一個佛教徒,我會在特定的日子齋戒,而當我作為一個上座部佛教僧侶時,遵守「不非時食」,即過午不食(但我可以喝東西!),所以長時間不進食對我沒有難度。挑戰其實是來自齋戒期間的禁喝,尤其是在土耳其炎熱的天氣下,我很快就變得唇乾舌燥,喉嚨乾燥得令我難以吞嚥。我需要經常舔自己的嘴唇,盡力去營造喝了水的感覺。我的組員們因此取笑我,用美味的食物和清涼的飲料引誘我,但我還是堅持下來了。

當我進食第一次的開齋餐,那種感覺難以形容,我喝了點水和吃了些棗,清涼的水流過我喉嚨的那股衝擊,加深我對喝水這個簡單動作的認識和珍惜。另外,我更加具體地感受到那些不如我幸運的人,在缺乏食物和水的情況下所受的如何的煎熬;這便是我即時意識和覺察到的切實反應,我每晚開齋時的體會。

齋戒不久後,我就建立了一個規則的作息時間,每天早上三時起來進食封齋飯,然後閱讀一下《可蘭經》的經文,到早上四點再睡。我的封齋飯非常簡單,包括水果、餅乾、水和乳酪飲品。有幾次,當我隨當地的穆斯林一起進食時,我的封齋飯才比較豐富。而在每天的開齋飯,我謹記不能狼吞虎嚥,否則將令齋戒失去意義;我只吃下剛好讓我感到舒服的份量,讓自己有三分之一的飽腹感就好。

我們亦曾經作客別人的家中,或是在比較大型的公眾場合如學校等,與學校的職員或一些家庭一起吃開齋飯。我想在這裡補充一下,回港後,我曾與我的學生 阿里(Ali) 到九龍清真寺吃開齋飯。那裡的用餐區非常擠逼(男性和女性是分開進食的)。伊瑪目領禱後,我們才開始進食。這開齋飯是我吃過最簡單的,但同時又非常獨特,是我吃過的開齋飯當中最具意義的。那裡的食物很普通:只有Halim(一種湯)、咖哩角和果汁。吃過開齋飯後,有些信徒上樓作晚禱,有些人則繼續留在用餐區。他們把椅子移開,然後站成一排排,一起祈禱。他們對伊斯蘭教的誠懇和投入,是最為顯著和最動人的。

在土耳其的每個角落,我都受到熱情和仁慈的對待。我常常以“ Wo assaloaleikum” 這個象徵和平的打招呼方式問候他們,而當他們發現我也在禁食的時候,都會流露出好奇和欣喜。在這次旅程中,我與接待我們的穆罕默德先生(Mehmet)、約瑟夫先生(Joseph)及耶爾巴依先生(Yelbay)一起齋戒(但當中有人曾因病而暫停一天)。他們在我齋戒的頭幾天都感到十分驚訝,而且極其殷切地關注我的健康狀況。他們每天一早開始守齋時都會問我會否繼續禁食,但我的態度非常堅定。與此同時,我的室友勞里(Lauri)說他會齋戒一天,但他非常狡猾(或者可以說是幸運),因為他選擇了在我們大部分時間都待在冷氣車上以及睡覺的一天進行齋戒。我嘗試勸他繼續齋戒,但他拒絕了,只說他將繼續維持素食的習慣。

當我回到香港後,我還繼續齋戒月的禁食,所以我總共齋戒了25天。明年的齋戒月,除了禁食,我亦打算奉行伊斯蘭教的傳統,於齋戒月期間盡力讀畢整部《可蘭經》。

圖、文:約翰.坎農 (John Cannon) 翻譯:Tong Wing Man

2012-10-15

- The Turkish “Great Teacher” ─ Fethullah Gülen and his Amazing Social ReformsPearl Institute2017-06-06T11:38:11+08:00

- Themes of Dialogue “Even if We Have Different Color, but We are the Same”Pearl Institute2017-06-06T11:38:11+08:00

- Editorial – Themes of Dialogue: Turkish culture, Buddhism, and Muslim friendshipPearl Institute2017-06-06T11:38:11+08:00

- Intercultural trip to Turkey with the Academicians and Students of Chinese U of Hong KongPearl Institute2017-06-06T11:38:22+08:00

The views and opinions expressed on this posts/pages are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of Pearl Institute, its staff, other authors, members, partners, or sponsors.

Leave A Comment